Alberta’s disability-income policy keeps people poor. Rather than stacking the Canada Disability Benefit atop provincial supports, the government deducts it from AISH and is launching ADAP, a lower-rate program for people labeled able to work. These choices manufacture scarcity, expand paperwork, and shift costs to hospitals, shelters, and municipalities. AISH recipients are required to apply for every program—including the CDB—only to watch the benefit clawed back. This section explains how the scheme works, why Alberta is an outlier, the damage it causes, and the fixes we’re demanding to restore dignity, stability, and poverty reduction.

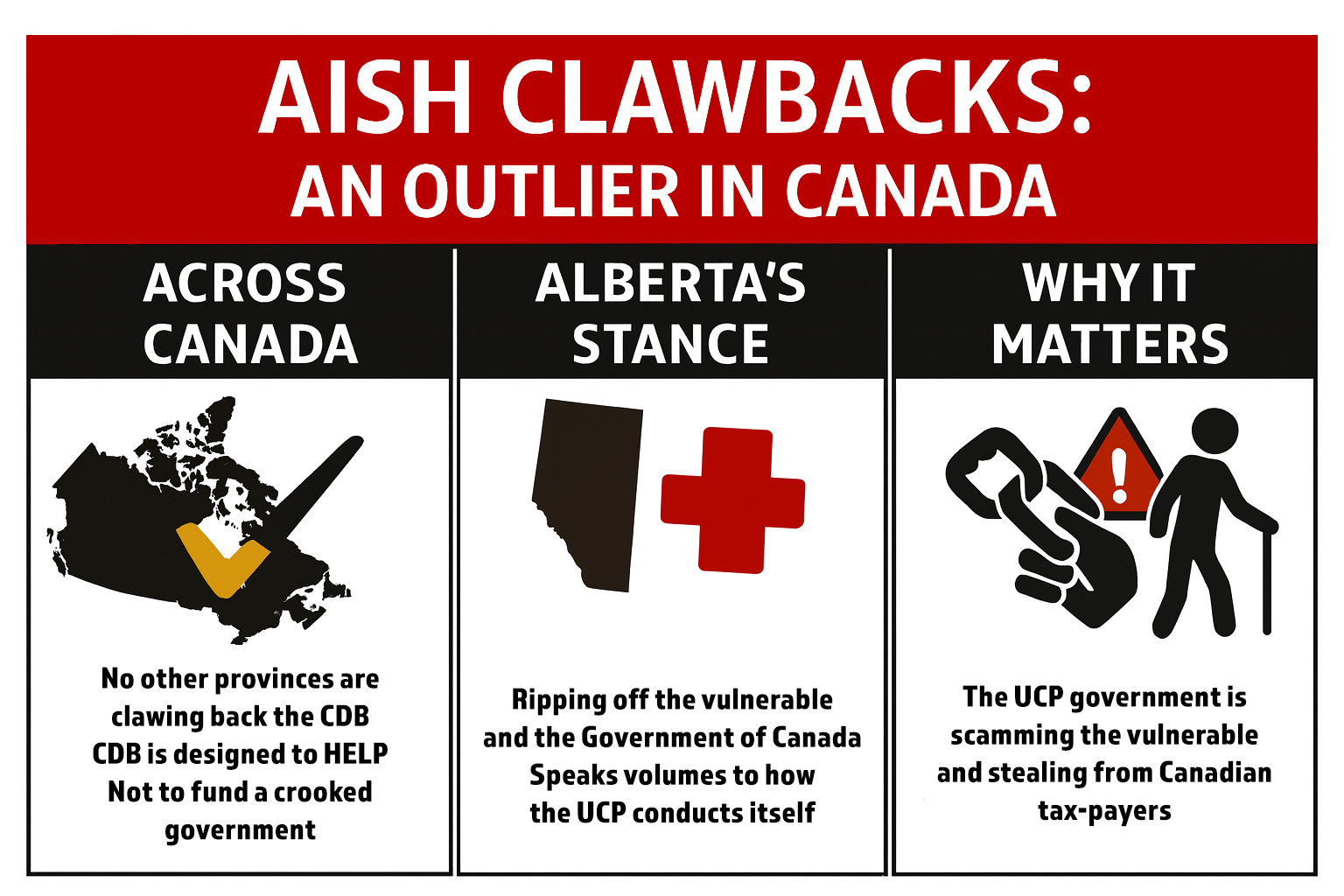

Across Canada, provinces pledge not to claw back the Canada Disability Benefit or carve exemptions so the federal top-up sits on top of local supports. Alberta moves the other way, deducting the CDB from AISH and launching ADAP with a rate about $200 below AISH for people deemed able to work. This combination signals: if you secure federal help, the province will take it—and if you can work, you’ll be shifted to a lower program. It isolates Alberta from emerging national norms, confuses interprovincial moves, and brands the province as balancing budgets on disabled people’s backs.

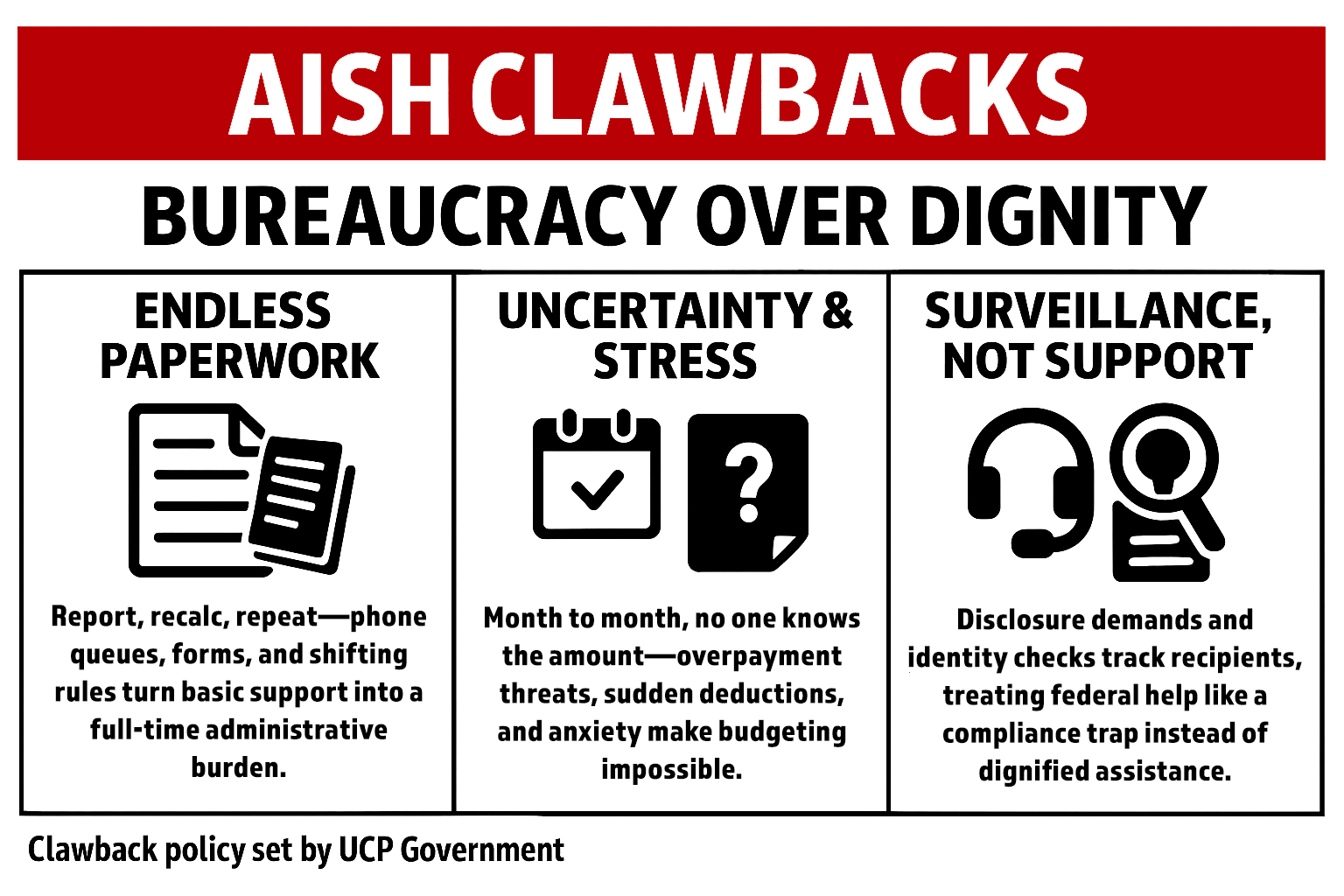

Clawbacks don’t just shrink wallets; they expand bureaucracy. People must disclose federal payments, brace for recalculations, and fear overpayment letters if a form is late or a rule shifts mid-stream. Month to month, no one knows what will land in the account, making planning impossible. The churn becomes its barrier: phone queues, daily appointments, and letters in bureaucratese that demand time, energy, and transit money. For many, disability already requires documentation; the clawback adds a surveillance layer treating federal support like a compliance trap. Policy should deliver stability and dignity, not paperwork marathons or anxiety over administrative mistakes.

Follow the emerging national standard: no clawbacks. Exempt the Canada Disability Benefit from AISH calculations automatically—no forms, no gotchas—and make the change retroactive where needed to erase “overpayment” debts. Publish plain-language guidance so recipients and workers share the same rules. Index AISH to living costs so federal gains aren’t swallowed by inflation. Co-design implementation with disabled Albertans, require regular reporting, and legislate a prohibition on offsetting federal disability benefits with provincial deductions. In short: let people keep the full federal amount, stabilize income, reduce administrative churn, and build a benefits floor that ends disability poverty.

The Canada Disability Benefit was designed to sit atop provincial supports and reduce disability poverty. Alberta does the opposite: it treats the CDB as income and deducts it from AISH, turning a federal top-up into a provincial saving. People apply, qualify, and report—then watch the “increase” vanish at the ledger. Alberta is also introducing ADAP for people labeled able to work, with a rate about $200 lower than AISH—another subtraction. Policy should stack supports to reflect costs of rent, food, medicine, and mobility, not zero-sum accounting tricks that keep people treading water while governments claim prudence.

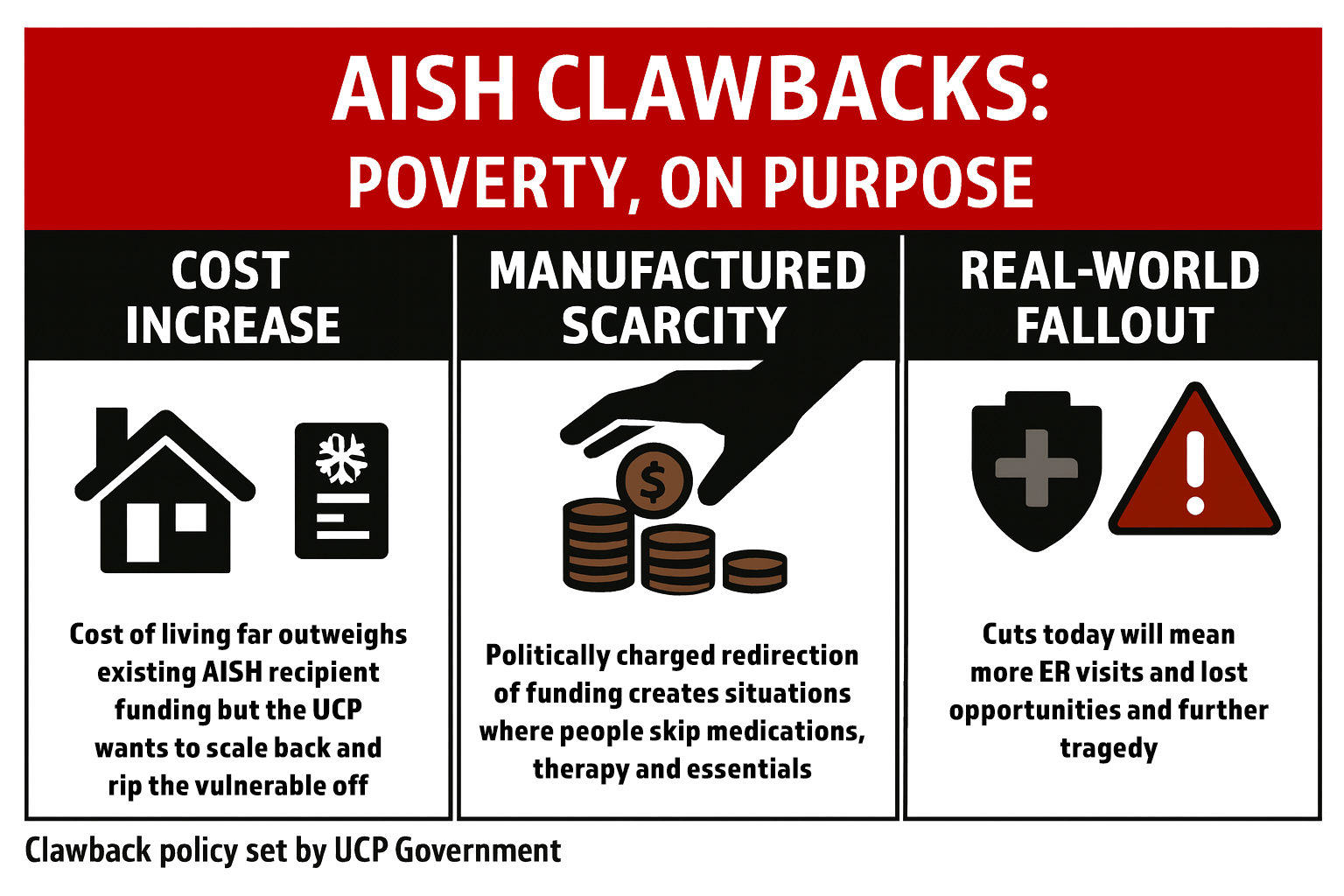

Clawbacks keep people where policy says they shouldn’t be: in chronic poverty. Every bump—rent hikes, winter power bills, a broken mobility aid—becomes a cliff when the top-up is subtracted. The Canada Disability Benefit was meant to soften those edges; Alberta’s deduction turns them into walls. Poverty isn’t low income alone; it’s volatility, stress, and triage harming health. When “extra” dollars are clawed back, people delay medication, skip therapy, ration food, and fall behind on utilities. This isn’t prudence; it’s manufactured scarcity, with bills hitting hospitals, crisis housing, and opportunity lost too.

On paper, clawbacks look like savings. In reality, they push costs and multiply harm. When people can’t afford basics, systems pick up the tab: emergency rooms for unmanaged conditions, shelters and policing for housing precarity, crisis grants and food banks filling gaps. Administrative costs rise too—reassessments, appeals, and error corrections aren’t free. Meanwhile human toll—lost work or school, family strain, worsening mental health—drags economy. Real savings come from lifting income floors so crises are prevented, not treated. Clawbacks do the opposite: austerity at the front door, higher costs at the back, with suffering in between.